Tim Errington

Tim ErringtonTen years ago, COS began its mission to transform the global conduct and sharing of scientific research. The vision is a world where scientific knowledge flows freely, research is transparent and verifiable, and collaboration thrives across borders and disciplines.

Scientific knowledge is built upon the accumulated foundations of past discoveries. Each new investigation refines, challenges, and ultimately shapes our understanding of the world. The integrity of this process rests on unfettered access to the underlying information that fuels scientific inquiry. Without access to data and code, evaluating the credibility of research findings becomes challenging. This lack of transparency hinders self-correction, preventing independent verification and potentially leading to inaccurate research.

Since the founding of COS, researchers have made progress in improving the credibility of research across disciplines. However, there is still a need for a more comprehensive assessment of credibility. Four approaches to credibility assessment — process reproducibility, outcome reproducibility, robustness, and replicability — show there is room for improvement across research disciplines.

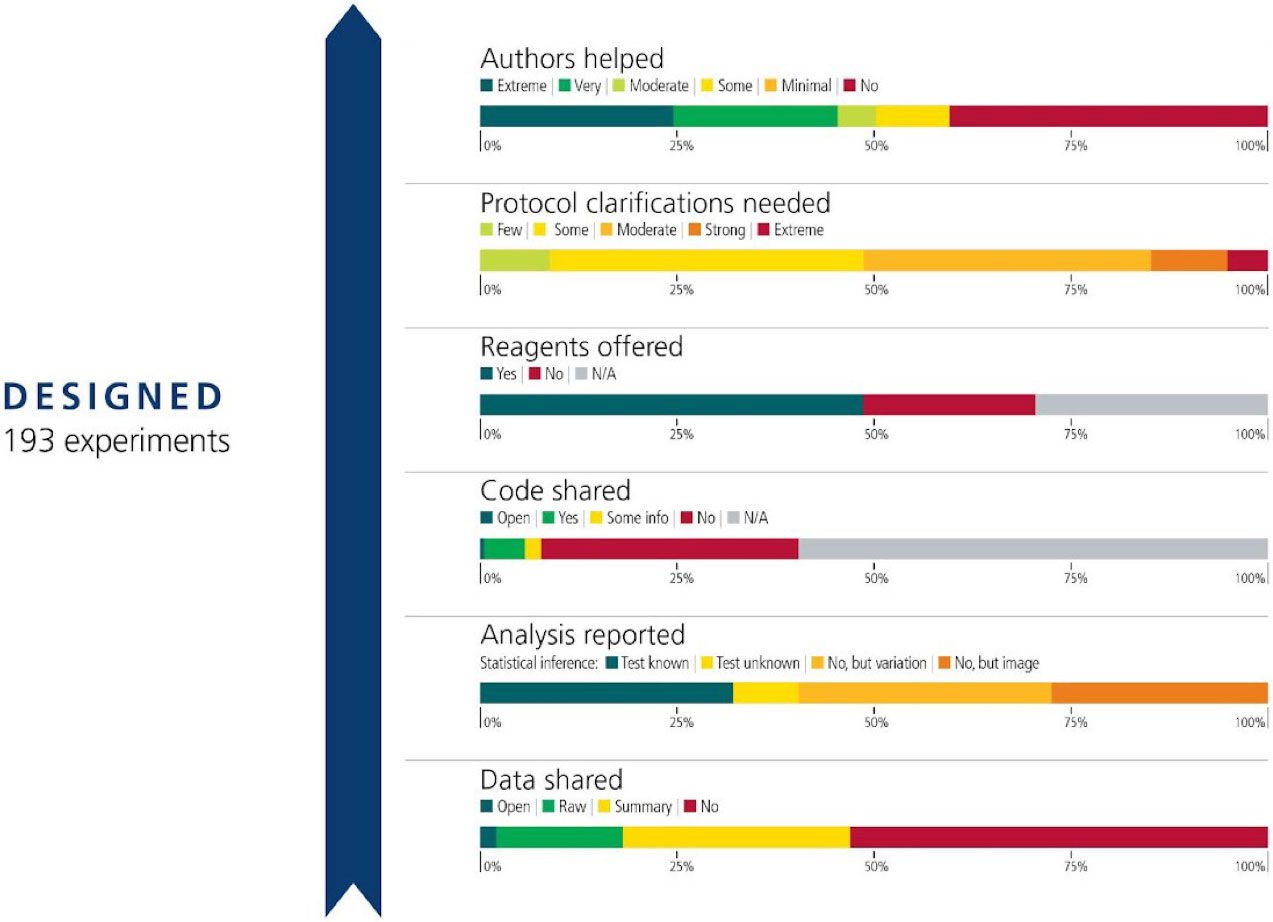

Making underlying data, code, and materials available for verification fosters trust and validity. Process reproducibility probes the accessibility of underlying materials. Studies across diverse fields reveal widespread areas for improvement in data sharing. For example, a study analyzing researchers’ compliance with their data availability statements found only 7% of authors shared data upon request (Gabelica, 2022), and the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology revealed significant barriers to accessing research data and materials. This lack of transparency hinder the self-corrective process of science, preventing independent verification.

Analysis of researcher compliance with data availability statements

Testing outcome reproducibility involves attempting to repeat the original findings using the same data and analysis. It assesses whether the findings and the analysis to obtain those findings were reported accurately. In principle, the success rate for reproducing study outcomes should be 100 percent but falls short of that across fields. Failing to share original data and process reproducibility prevents the assessment of outcome reproducibility. Sharing the analysis code should make it easier to achieve outcome reproducibility.

But even sharing original data and code is not sufficient to guarantee outcome reproducibility as observed in studies across economics, cognitive science, healthcare, and other disciplines. The REPEAT Initiative, for example, looked at the outcome reproducibility of claims using electronic health records. The study found that while original and reproductions were positively correlated, there was variation, sometimes quite extreme, indicating room for improvement.

Reanalyzing the same data with alternative analytical strategies can demonstrate the consistency of findings. A variety of studies in different fields have explored how variations in analytic choices affect results. For example, one study explored the potential influence of analytical choices by having 29 teams analyze the same soccer referee bias data. The outcome was a wide range of findings, with roughly two-thirds significant and positive results, but one-third observing null results. This variability, often invisible in single-analysis papers, reveals the need for greater transparency and consideration of alternative approaches.

Replicability refers to testing the same question as an earlier study using new data. It is ordinary in science for some promising initial findings to be much more limited than initially expected or even to be false discoveries. However, without an ethos of conducting replications, there may be false confidence in the strength and applicability of earlier claims. For example, the Reproducibility Project: Psychology attempted to replicate 100 high-profile findings. The results showed only 36 percent replicated with statistical significance in the same direction, and the effect sizes of the replications were half of the original effect sizes. Clarifying the replicability of findings, and the conditions necessary to obtain them, will reduce waste in building on research or translating it to application before its credibility is clear, such as investing in drug development without verifying that the preclinical evidence is credible and replicable.

These findings highlight the need for a multifaceted approach to bolstering research credibility. Crucial steps include increased transparency through data and code sharing, standardized analytical protocols to mitigate the influence of analytical choices, and the creation of a culture of independent replication. Doing so can enhance the credibility of scientific knowledge and accelerate the pace of discovery.

6218 Georgia Avenue NW, Suite #1, Unit 3189

Washington, DC 20011

Email: contact@cos.io

Unless otherwise noted, this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

Responsible stewards of your support

COS has earned top recognition from Charity Navigator and Candid (formerly GuideStar) for our financial transparency and accountability to our mission. COS and the OSF were also awarded SOC2 accreditation in 2023 after an independent assessment of our security and procedures by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA).

We invite all of our sponsors, partners, and members of the community to learn more about how our organization operates, our impact, our financial performance, and our nonprofit status.